5th City 20 Year Anniversary (1983) narrated by Ophrah Winfrey

AI NOTEBOOK LM DIALOGUEwith related INFOGRAPH

BACKGROUND

NAME ORIGIN: 5th City first took its name from 5th Avenue, the northern boundary of the community. Later, the name came to symbolically refer to any community that made a comparable decision to assume full responsibility for its own future.

GEOGRAPHY: Fifth City was the first Human Development Project developed by the Ecumenical Institute. It was located in a 16-block area on Chicago’s West Side, four miles directly west of the Loop.

CHALLENGES: In 1963, the community had high crime and unemployment, abandoned housing units, inadequate public services, deteriorating schools, few locally owned businesses and little access to healthy foods.

ACCOMPLISHMENTS

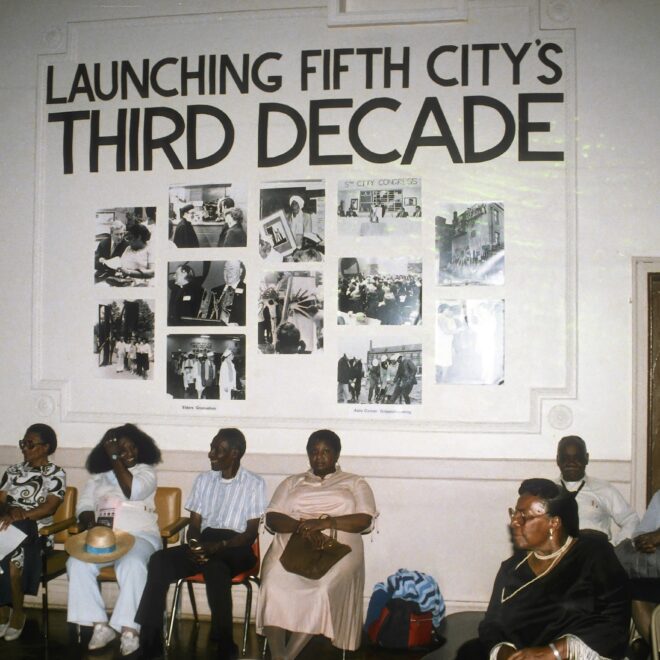

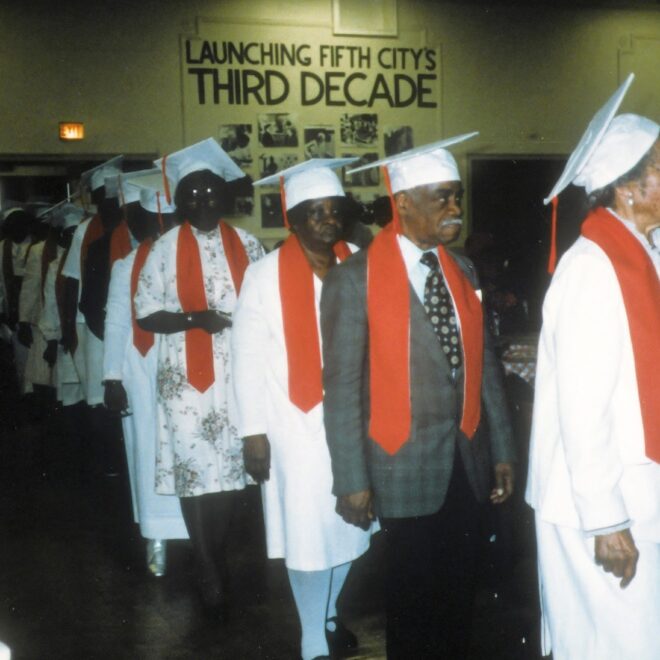

By 1980 5th City had celebrated the following accomplishments:

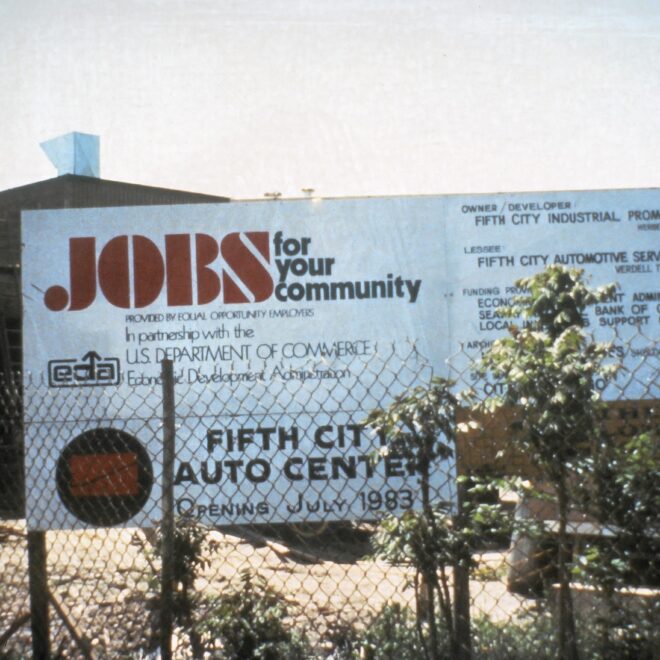

- The locally owned and managed shopping center had completed its fifth year of operation serving as the business center of the community.

- Investments of $470,000 have been secured for 5th City from the private sector in loans and contributions, and from the public sector in grants, loans and contracts.

- A community operated housing service had increased rent collection by over 90% and trained its staff in housing maintenance.

- 5th City was recognized throughout Chicago and the world and regularly called to host local, national, and international visitors, and to teach the methods of self-help to other rural and urban communities.

- In 1976 the establishing of the Men’s Club and the Safe Streets Patrol signalled a new volunteer role of male leadership. 28 men voluntarily served on community corporation boards and events.

The 5th City Journey

- 5th City Preschool – became one of the top 10 Headstart preschools in the nation

- Quarterly Congress: 3rd September 14, 1968; Presidium December 12, 1968; 5th December 14,1968; Presidium March 11, 1969; 6th October 11, 1969; 8th Congress September 30, 1969; Presidium December 9, 1969

- 5th City Actualization Problem Solving Unit, December 1969

- Citizens Redevelopment Corporation, November 13, 1969

- Demonstrating Comprehensive Community Development, John Baggett, 1969

- 5th City Education Plan 1968

- 5th City Reformulation: Vision and Model, December 1968

- 5th City Progress Report on the Board of Managers, November 1, 1968

- Fifth City U.S. Senate Testimony, April 17 1968

- Future is Open: 5th City Structures, 1968

- Fifth City Instructions, George West, Summer 1967

- Fifth City Story, 1966

- 5th City Urban Reformulation Model, 1965

- 5th City Citizens Redevelopment Corporation, 1965

- 5th City as Symbol, Summer 1965

- US Senate Hearing: Committee on Government Operations, introducing comprehensive approach to community development (November 1969)

- Quarterly Congress: 3rd September 14, 1968; Presidium December 12, 1968; 5th December 14,1968; Presidium March 11, 1969; 6th October 11, 1969; 8th Congress September 30, 1969

- 5th City Actualization Problem Solving Unit, December 1969

- Demonstrating Comprehensive Community Development, John Baggett, 1969

- 5th City Education Plan 1968

- 5th City Reformulation: Vision and Model, December 1968

- 5th City Progress Report on the Board of Managers, November 1, 1968

- Fifth City Testimony Document, April 17 1968

- Future is Open: 5th City Structures, 1968

- Fifth City Instructions, George West, Summer 1967

- Fifth City Story, 1966

- 5th City Urban Reformulation Model, 1965

- 5th City Citizens Redevelopment Corporation, 1965

- 5th City as Symbol, Summer 1965

- US Senate Hearing: Committee on Government Operations, introducing comprehensive approach to community development (November 1969)

- Fifth City, Image

- 5th City Voice 1974-1981: 1967, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1973, 1974, 1975, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979, 1980, 1981

- 5th City HDP Bulletin, selected issues 1976-1977 and February 1977

- 5th City Human Development Training School, December 1979

- 5th City Organizational Chart, November 1979

- Fifth City HDP Report, Verdell Trice, July 4, 1979

- Fifth City Red Book, December 1979

- Fifth City Town Meeting, January 24, 1979

- Fifth City Red Book

- Sen. Charles Percy Remarks at 5th City Anniversary Celebration, June 17, 1978

- 5th City Accomplishments, 1977-1978

- 5th City Annual Report, 1977-78

- 5th City Phase I Miracles, Phase II October Report, Phase III Compilation of Weekly Reports, October-November 1976

- 5th City to the World: HDP Connections, 1976

- 5th City Annual Report, 1976 and Report and Projection 1976

- “Start Small, Conquer the World”, Chicago Magazine Article, August 1976

- “Stakes, Guilds and the Community Congress“, Global Council, July 29, 1976

- Fifth City Demonstration of Global Community Forum, July 23, 1976

- Fifth City Workday Instructions, George West, Summer 1976

- Shopping Center Report, to the Methodist Church, June 1976

- 5th City Report Phase I, May 30, 1976

- Fifth City Community Assembly, May 16, 1976

- Fifth City HDP Consultation Summary Statement, April 1976

- Fifth City Consult Prep

- 5th City Annual Report, 1975

- 5th City Comprehensive Situation, December 9, 1975 and here

- 5th City Citizens Development Corporation: Reorganization Plan, December 1975

- Rebirth of Community, Mayor Daley, 1975

- “5th City Commissioning Report“, Lela Mosely, GRA, July 27, 1974

- “Fifth City: A Sign of Hope“, Joseph Slicker, January 1974

- Fifth City Decade Celebration, 1974

- Fifth City: A case study in human development, Joseph Mathews, Jr, 1973

- Mayor Daley Remarks “From a Grateful City”, 5th City Decade of Miracles Celebration, December 15, 1973

- 5th City Social Model, November 1973 and Report, November 24, 1973

- Preparation for Second Decade, October-December, 1973

- Quarterly Council Report, April 25-27, 1973

- 5th City Report, Chicago Regional Council, December 2, 1972

- Fifth City Environmental Campaign

- Fifth City Beautification Book

- Fifth City Social Model and Community Organization

- Fifth City Beautification Book

- 5th City Celebrates Three Decades, Spring 1994

- 5th City: A Community in Motion, 1993

- Chicago Defender news article, January 13, 1986 and other articles 1967-1983

5th City Revisited, a play by Meida McNeal wrote in 2019, tells the story of 5th City’s community development days in the 1960s and 70s and what has happened to it in years since, raising questions about where community residents want to go next. Meida, the daughter of Judy Gritzmacher and George McNeal, was born in 5th City and attended the 5th City preschool. She now directs her own art company, Honey Pot Performance, and works for the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs. Meida was interviewed by the Newberry Library regarding telling the 5th City story: “Signs of Creative Resistance: Chicago’s Fifth City Movement”. McNeal, Meida presents “Fifth City Revisited”2023 and here in 2019.

Denise Gathings, a Chicago police officer and daughter of Ruth Carter, the 40-year director of the 5th City Preschool, wrote and directed My Soul Cries Out: Stop! and here about gang violence. In May 2017 the play was held at the ICA GreenRise.

5th City Iron Man Plaza: Placemaking in East Garfield Park, Chicago Department of Transportation, 2017

Jean Loomis tells the history of the Iron Man statue that she designed in 1968